Today you’re in for a treat.

Jamie Keech, who joined our merry band of men here some months back, is uniquely positioned to bring much, much more to the table than I ever could when it comes to the commodity spectrum. It’s why, quite frankly, we wanted him.

But aside from his dashing good looks, he’s also a mineral engineer who spent the early part of his career working in exploration in Mexico, Nevada, the Yukon, and Albania.

He went back to school, completing a Masters in Mining Engineering focused on Environmental Development and Corporate Social Responsibility at the Camborne School of Mines in the UK. Jamie then moved to Hong Kong and Mongolia working for the world’s largest mining contractor, Leighton Holdings, on three open-pit coal mines. He then returned to Toronto and spent two years working with Hatch Consulting, a leading global engineering firm, where he was focused on ArcelorMittal’s $6-billion Mary River iron ore project in Nunavut.

When he joined our merry team he was, and still does conduct due diligence on behalf of mining investors, and consults to various junior companies on technical due diligence, project management and regulatory affairs. As if this wasn’t enough he has taught an introduction to mining at Nanjing University in Nanjing, China and seminars for P.W.C. on the technical aspects of mining.

All in all, he’s very switched on and a great resource for all of us as well as you, our readers.

This article is Jamie’s first pubic appearance if you will. I think you’ll like it.

– Chris

————

Nickel

Henry Ford once said: “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.”

Steve Job’s mused people don’t know what they want until you show them.

It’s become a common ethos in Silicon Valley and the tech world that innovation comes from individual creativity as opposed to the group demand, and it is the rare visionary that can tap into this societal zeitgeist and create something before we know we want it. It’s even more rare to find someone that can take a common substance and make us need it.

You don’t know who Robert Crooks Stanley is.

His product is common to the point of mundane. But in addition to being essential, it’s prolific.

Until the 20th century nickel was used for making one thing: Nickels.

However, this all changed when it was discovered that steel made with nickel was extremely hard and durable. This discovery coincided neatly with the assassination of a certain Archduke which thereby resulted in an unprecedented global demand for very hard steel – primarily for armored plating (tanks, warships, etc.).

When international disarmament began in 1921 the price of nickel was decimated.

No one was harder hit by this than the International Nickel Company, more commonly known as INCO. INCO controlled North American nickel production most of which came from the famous Sudbury Basin. With dwindling demand for its product INCO suffered an existential crisis and the mines of Sudbury were silenced, allowing stockpiles to dwindle.

INCO drew two conclusions from the experience:

- If INCO was going to succeed they would need to control the supply to the market;

- They were going to need to find something else to do with nickel.

Enter Robert Crooks Stanley.

During his 30 years as CEO and Chairman of INCO Stanley literally created the nickel market. Driving millions into R&D he found uses for a product no one knew they needed.

Why do we have nickel in your stainless steel? Stanley.

How about home appliances? Jet engines? Power plants? Stanley.

Essentially every innovation in the nickel industry for 50 years was developed by INCO engineers. They shared their innovations with customer and competitor alike – if it drove demand for nickel they didn’t care.

They did something else as well: They controlled supply.

INCO controlled the stockpiles and the prices. If a competitor attempted to enter the space they flooded the market, dropped the price and crushed them. By the 1930’s the demand for Nickel had returned to prewar levels and INCO dominated the market – Controlling 90% of the non-communist world’s production.

But as the Iron curtain fell unleashing massive competitors, and the demands of a growing Asia drove prices, INCO was unable to control the market. After 50 years of reigning supreme their market share dropped to under 30% and in 2006 they were taken out by Brazilian mining giant Vale.

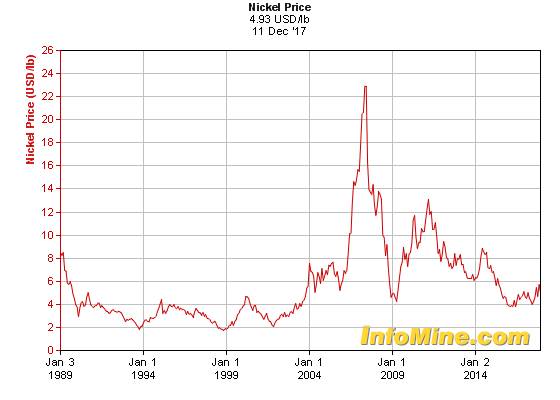

After the boom in the early 2000’s nickel sits at nearly a 20 year low:

But, it’s starting to look like another would be visionary could be driving the nickel price for the next decade.

History does not repeat itself, but it often rhymes

– Mark Twain

Whether you believe Elon Musk is going to save the world, or has created one of the greatest short opportunities in history is irrelevant. He’s begun an arms race in the electricity storage industry.

As a secondary effect, he appears to be one of the greatest mining promoters in history, having almost single handedly ignited the boom in the lithium and cobalt space in recent years.

But here’s the thing: Tesla’s lithium-ion NCA battery is composed of 80% nickel.

Our cells should be called Nickel-Graphite, because primarily the cathode is nickel and the anode side is graphite with silicon oxide… [there’s] a little bit of lithium in there, but it’s like the salt on the salad.

– Elon Musk

Similarly, both Chevrolet and Nissan utilize substantive quantities of nickel in their EV cathodes.

Nickel price is driven by three factors: War, Development, & Innovation

Today the nickel market is worth an estimated $20B, this is primarily driven by the manufacture of stainless steel. The price boom of the early 2000’s was catalyzed by development in China – the next will be driven by EV innovation.

Today electric vehicles comprise about 1% of cars on the road – their batteries demand 70,000 tonnes of nickel per annum, a mere 3% of the global market.

Countries throughout Europe and Asia (UK, France, India) have made plans to ban or limit the use of fossil fuel burning vehicles over the coming two decades. Even China has made grumblings about banning gas fueled vehicles.

Major mining companies are starting to move to secure their place in the market. In August BHP Billiton announced it would be spending $43.2m to build the world’s biggest nickel sulfate plant.

Ivan Glasenburg, CEO of mining and trading giant Glencore stated that:

A shift of just 10% of the global car fleet to EVs would create demand for 400,000 tonnes of nickel, in a 2 million tonne market. Glencore sees nickel shortage as EV demand burgeons.

The banks are starting to take note with CIBC’s, Wood Mackenzie stating:

Although the capacity to produce nickel sulfate is expanding rapidly, we cannot yet identify enough nickel sulfate capacity to feed the projected battery forecasts.

The junior explorer and small cap investors are just beginning to wake up to this trend. In Canada Garibaldi Resource has been on a run the past 6 months on the back of some decent drill results from their aptly named Nickel Mountain Project.

With little evidence to date Garibaldi is being heralded as the next Voisey’s Bay, the nickel discovery that made infamous mining promoter Robert Friedland his (first) fortune.

I read these movements as a shift in investor confidence on nickel and believe it indicative of more to come. Recall that it was the discovery of Voisey’s Bay in the 1990’s and its subsequent $4.5B sale to INCO that has largely been credited with igniting the mining/metals mania of the early 2000’s.

Tesla entered the EV market in 2003, but it wasn’t until 2015 that the lithium price took off; the assumed future demand for lithium sending every junior mining promoter first to Nevada, than Argentina, and now anywhere with the faintest whiff of lithium brines. This process is repeating itself with cobalt.

So why lithium, or cobalt, when a lithium-ion battery is 80% nickel?

My guess is twofold.

First, both metals are produced in such small quantities that the idea of crises level shortages on the horizon is easy to swallow. With cobalt produced primarily as a byproduct of Congolese copper mines, and the U.S.’s entire lithium production coming from a single operation in Nevada it is easy to wrap one’s mind around the concept of scarcity.

Second, no one has managed to lose money on lithium. Although you certainly couldn’t accuse mining promoters of having a long memory there is something unique about a metal that almost no one has managed to go broke on (yet). Nickel, like most metals, has a long and sordid history; and carries with it the emotional baggage of going through a century of metal cycles.

Lithium and Cobalt on the other hand hold the unusual position of being “new”, or better put: exotic. Almost no one knows anything about them so they can believe whatever they want, or rather, whatever they’re told.

Not so with nickel (or copper, or zinc, or gold, for that matter).

Investors have had many opportunities to lose money on nickel; and no doubt many have taken those opportunities. But there have been just as many opportunities to make money.

The key to successful speculation in the mining space in timing cycles. The nickel price is driven by war, development and innovation. With the global EV industry approaching a tipping point, continued growth in China and no apparent shortage of war on the horizon investors looking to capitalize on these events should remain watchful of nickel.

– Jamie Keech

“A nickel ain’t worth a dime anymore.” — Yogi Berra