Today we’re hearing from our resident mining guru, Jamie Keech. Jamie’s previous article on a bull market in nickel was well received, and today he delves into some key principles for every resource investor.

– Chris

————

Let’s start with a quote:

“For to everyone who has will more be given, and he will have abundance; but from him who has not, even what he has will be taken away.”

— Matthew 25:29, RSV.

Harsh Jesus, harsh.

For every Bible pounding Christian out there, it offers some uncharacteristically tough love from the Savior and for every indignant atheist, a nay missed opportunity to point to some theocratic hypocrisy.

But regardless of your views on immaculate conception (I think we can all agree it’s less fun) perhaps that clever little middle-eastern carpenter was onto something:

The Matthew Effect

Maybe he was just telling it like it is?

Enter: sociologist Robert K. Merton who, based on the above bit of scripture, coined the term “The Matthew Effect” a rather elegant way to say: The rich get richer and the poor… do not.

Or perhaps better put: to win once begets the likelihood of winning again.

We all know that inequality is a fact of life, and as they say “to the victor go the spoils”.

The Pareto Principle in Mining

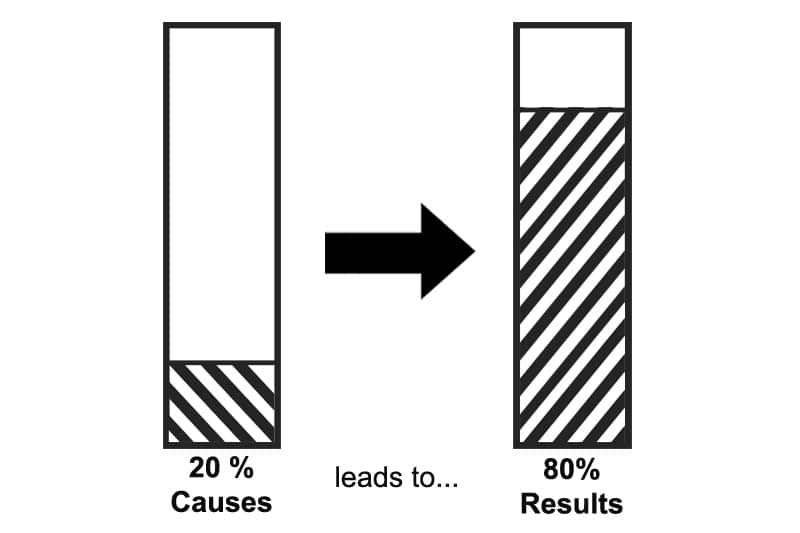

The most famous iteration of the Matthew Effect is the Pareto Principle, commonly known as the “80/20 Rule” as demonstrated by Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto.

The idea originally pertained to the creation and distribution of wealth, stating that 20% of a given population is responsible for 80% of the output, and the other 80% is more or less useless unproductive hangers-on. If you’ve ever had a job you can probably attest to this, and if you can’t… well, then you know which group you fall into.

Pareto first demonstrated his rule by showing that 80% of the land in Italy was owned by 20% of the population. It has since been extrapolated across disciplines such as academic citations, book sales, and hits songs. Pretty much everywhere.

So on average, 80% of the wealth is captured by 20% of the bankers or 80% of toilets are fixed by 20% of the plumbers, or 80% of green beans grow on 20% of the vines. And nowhere does the 80/20 Rule ring more true than the mining industry.

Bet the Jockey

An oft-quoted maxim amongst speculators is “Bet the Jockey”. This means that when choosing a stock, bet on the team, not the project. The heuristic stems from the belief that the best management teams will get the best projects, and that the average investor is more able to judge the caliber of an individual (and their track record) than a mining project.

Occasionally this method seems to work out:

- David Lowell has discovered over a dozen mines, including some of the world’s biggest, and generated billions for shareholders.

- Lukas Lundin and his family have created a mining empire that spans the globe consistently turning around projects where others (sorry Kinross) have failed.

- Robert Friedland has made discovery, after discovery after discovery and raised billions for exploration cementing himself as not only the greatest promoter of a generation but one of the most successful explorers in history.

Now Come The 80%

Then there is pretty much everyone else.

While there are huge wins to be had, most mining companies spend their time doing what mining companies do best: wasting cash.

There are a lot of reasons for this: management is often incompetent, or the geological concept doesn’t quite pan out, or the market turns against them, or metal prices drop and then slowly (or quickly) the company ceases to exist.

Even the winners rarely spend much time on top.

A seldom-discussed aspect of the 80/20 Rule and one conveniently overlooked by the SJW’s constantly banging the inequality drum is that turnover at the top is very high. While there is always a small number of people that control a large amount of money/power/prestige/etc. it is rarely the same person for long.

- The average CEO in the UK spends less than 5 years on the job and according to the Harvard Business review 52% of Fortune 500 Companies have gone bankrupt in the last 18 years (remember when Blockbuster was a thing?);

- Italy has churned through 65 governments in the last 72 years;

- And 70% of rich families lose their wealth by the 2nd generation (90% by the 3rd!!).

It’s common to the point of cliche to see a management team come off a big discovery only to flounder and disappear on the next bigger/better project. The obvious (and hotly denied) reason is that most discoveries are not a result of visionary leadership or ingenious ideas, rather something far more common: Luck.

Let an infinite number of monkeys pound on an infinite number of typewriters for an infinite amount of time… one of them is going to knock out Hamlet.

And eventually, someone is going to find a gold mine.

The most interesting thing about the 80/20 Rule is that it works across scale. That means 20% of the top 20% accounts for 80% of its value; or put simply: 4% accounts for 16% of the total value creation.

So how do we control for luck? Sort out the monkeys from the serially successfully? Find the top 4%?

Tolstoy said, “happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” I say “great management teams are alike, but the bad ones all suck in their own unique way.”

Here is what you should look for:

1. Have they done it before?

In his book, “Principles” Bridgewater founder Ray Dalio writes that when hiring someone he checks to see if they’ve done the job at least 3 times before.

This controls for luck. Anyone can get lucky once, the blessed twice… but it’s hard to do so a third time. Anyone who has pulled off three wins is more likely to be competent.

It’s also important to note if someone is in their domain of expertise. A mine is not a mine is not a mine. Finding a porphyry copper deposit in Alaska is not the same thing as building an underground epithermal gold mine in Peru. Ensure that a team’s track record is relevant to the job at hand.

After a person has had multiple successes another phenomenon begins to occur: People beg them to take their ideas. They line up to give them away because everyone has at least one good idea but almost no one can execute.

This inflow of ideas gives them access to opportunities that the unproven simply do not have.

2. Do they know how to fail?

One of the reasons that David Lowell has made more discoveries than anyone else is that he knows when to kill a project. If a target isn’t shaping up the way he expects, he kills it quickly and moves on to the next. He doesn’t spend 5 years (and millions of dollars) praying the next drill hole is the one that proves the theory – he moves on to something better.

Does management waste time on projects with no future? Have they killed projects in the past instead of wasting investors’ money? Did their first project just happen to be a big win?

These are things to look out for.

3. Do they only have one shot?

Things will go wrong. Definitely.

There will be delays. There will be cost overruns. There will be social issues. I’ve never heard of a project coming together without a complication. There are simply too many unknown unknowns in a mining project. Will the team be able to manage problems when they occur?

Do they have the budget to weather delays and setbacks? Do they have the faith of their backers and the ability to raise more money when they need it? Or are they banking on everything going according to plan?

Because it won’t.

4. Do their incentives align with yours?

People do what they’re incentivized to do. Period.

This means that the management teams’ incentives need to match yours. They must be meaningful shareholders, and their salaries should be good but not cushy. They need to win if, and only if, shareholders win.

If they have the opportunity to slowly dwindle away the cash in a plush office on $300k a year regardless of what happens to the project… you’re screwed.

5. Give credit where credit is due

For every successful project there are a dozen people who claim responsibility and leverage it for the remainder of their career; or in the words of JFK “Success has many fathers, but failure is an orphan”.

Don’t be fooled. Most big wins come down to the ability or the effort of one or two key people who get it over the line; everyone else is just helping. Just because someone is a good addition to a winning team does not mean that they can repeat the process on their own. From every successful team, you’ll get half a dozen spin-outs who try and do it themselves. Do your homework and be sure to give credit where credit is due.

Backing the right jockey won’t guarantee success. In fact, many of the best performers in the space have almost as many losses as wins on their cards. But the best people tend to get better opportunities and know how to make things happen when they get their hands on them.

What the Future Looks Like

Over the coming weeks, I’ll be digging into some of the best opportunities in the mining space. Undervalued assets, asymmetric trades and a proven management team (that meet my rules above).

We’ll look at:

- A largely unknown gold royalty company primed to grow 40% this year while pulling in $30M in revenue;

- a team of award-winning mine finders on the trail of the world’s next big copper belt;

- and how to get exposure to a skyrocketing group of metals that hardly anyone is talking about.

By identifying these leaders and exploring the opportunities, they’re creating investors that will be well ahead of the pack. And if that doesn’t work out, at least you’ll have Jesus on your side…

– Jamie

“In any field of human endeavor, some people succeed better than others. So, investing with people who have been serially successful is probably more important than any other single variable.” — Rick Rule