In part one we discussed the troubling issues in Europe (in case you missed it, you can read it here).

Today… Japan

The story of Japan is really a story that begins with globalisation.

According to the Oxford Dictionary, globalisation is described as:

“The process by which businesses or other organizations develop international influence or start operating on an international scale.”

It is, in a nutshell, international trade, and one of the things it’s done is add huge swathes of the global workforce to the world’s economy.

I bring up globalisation because of what it’s done to the global labour supply.

Realise this labour supply wasn’t Joe-middle-class-Sixpack with a Beemer, a two story house in the suburbs, and a white picket fence.

When most people think of this workforce, they picture small brown people in shabby clothes toiling in sweatshops in China, India, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Cambodia, etc.

And by and large that’s it.

We’re not talking about Joe Sixpack. No, this was Amit in Bangladesh with 45 kids, working 29 hours a day, and paid the equivalent of a Happy Meal at Mackers.

And when we got such a massive disparity in costs, market forces went to work and did what market forces do.

The supply of goods produced exploded, and the cost of labour on a relative global basis fell.

I guess we could call this a labour supply shock, and what this did was it helped keep wages suppressed in developed markets while those in developing markets rose. This is how Amit raised his living standard so he can afford his 5th wife.

Now, the flip side of suppressed wages in the developed world was, of course, ever cheaper imported goods as the cost of those has plummeted. Declining real wages in the developed world have been cushioned by deflation in consumer goods.

So when the developed world looks about at all the cheap consumer goods they can so easily afford, they’re as happy as Michael Moore at a free buffet. What’s not so impressive is when looking at domestically produced goods — things such as healthcare, legal, and education.

Which is one of the reasons Joe looks around today and can’t quite figure out why he’s still got a bloody mortgage… and when he thinks about how he’s going to pay for his kids’ college, let alone his retirement, he decides instead to up his prescription of Xanax. This wee known fact is also incidentally one of the components that helped Trump get elected. For all his faults, he understood this.

The deflationary forces of this low cost labour have been exacerbated by companies arbitraging this labour. Often some have done this merely to survive but it’s created the setup where today we’ve global trade deficits looking the way they do.

In any event, what we need to understand is that all of this is clearly deflationary. The technological forces and globalisation which worked and work together in a positive feedback loop that is extremely deflationary.

A Bit of History

And this is where our sake-drinking friends come in.

In the 80’s, I was just a tot climbing trees and generally making a nuisance of myself, so I’ve no recollection of it, but we do have history as a guide. And from history we know that the 80’s belonged to Depeche Mode and Japan. Depeche Mode made taking drugs and looking morbid cool for millions, while Japan managed to eat the rest of the world’s economic lunch.

People will tell you it’s because they made cars that literally never break down, which is only partly true.

The fact is they perfected it with all manner of goods.

It is a perfect example of learning from the best to become the best. First, they copied and then perfected the West’s technology (incidentally much like China is doing today, but let’s leave that for another day) and they did so at a cheaper cost than the West could. A large component of that “cheaper cost” was a relatively cheap and highly educated workforce.

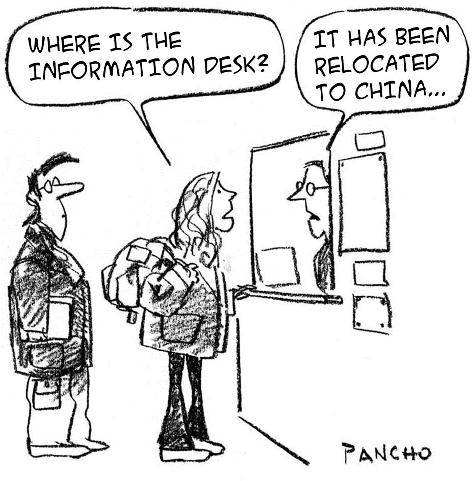

If you look at the chart above, you’ll see the massive bull run in the Japanese stock market, which lasted all through the 80’s. I picked the TOPIX here as a proxy, though the Nikkei tells much the same story.

What I found interesting is that it was the crash on Wall Street we all know as Black Monday that laid the foundation for the blow off top in Japan which came just two years later.

At the time of the crash, Japan was the largest holder of US debt. And so when Black Monday hit, it wasn’t just Wall Street traders panicking.

The Japanese, unsurprisingly, panicked right along with them, repatriating a lot of that capital. And it was this repatriated capital which then set the stage for the whopping blow off run in Japanese real estate and equity markets which topped out at the end of 1989.

Remember that as I’ll come back to it later… and how it may just relate to the fiasco currently developing in Europe.

Deflation

The puzzle that has perplexed some of the brightest fund managers of our time is the Japanese debt situation. You all know the basics….

Massive debt to GDP that’ll never be paid back, with the BOJ increasingly owning more and more of the bond market… yada, yada. I can’t add anything to all the obvious stuff you already have heard a thousand times.

The reasons Japan’s been able to get the monetary equivalent of an anvil to float mysteriously about like a helium filled balloon can be found by looking at a few things:

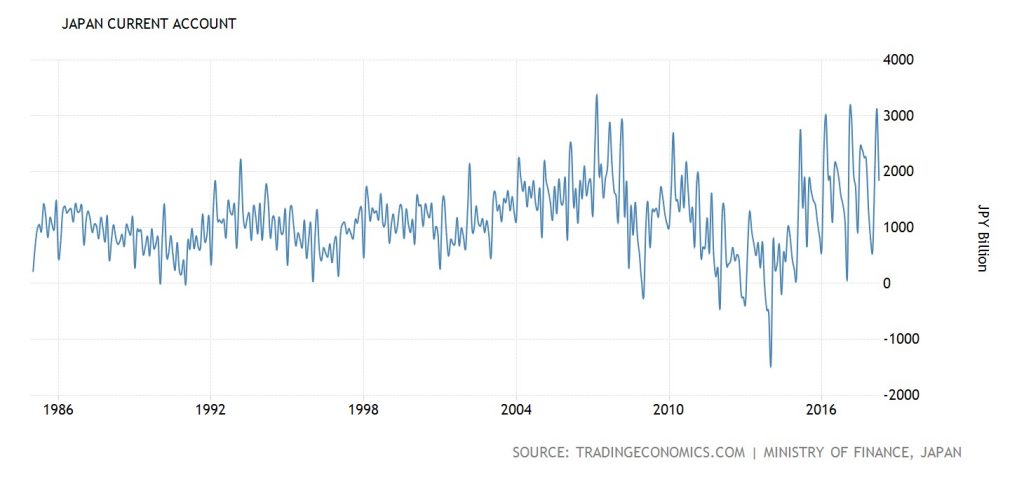

- Japan runs a current account surplus. This surplus can and is reinvested into the Japanese debt markets, meaning they’re not reliant on external capital to fund the government. Japan’s external debt to GDP is actually very low. It’s lower, for example, than the US, UK, Germany, France, and even China.

2. Demographically, Japan is in decline. This is one reason that we find GDP per capita in Japan is actually increasing.

Turns out putting about a million people every year in a box at a rate that’s faster than the economy’s declining means output per capita is increasing. In fact, Japan now has a labour shortage problem, which brings us to the next point.

3. Japan’s unemployment is now at record lows.

Back to Europe, which is conducting its own monumental monetary experiment.

Globalisation Reversing

Although the trend towards globalisation is a solid one, there have been some serious disruptions along the way. Sometimes they’ve been global, the two previous world wars being the most obvious. And other times they’ve been more self imposed: the USSR, Mao’s China, and Kim’s North Korea provide examples we all can relate to.

What we’ve had certainly in the last couple decades has been geopolitical harmony and increasing globalisation acting in a positive feedback loop.

Which brings me neatly to our present time where we are on the brink of an all-out trade war between the United States and the rest of the world. And of course, it’s not just the US.

I pointed out some issues in Europe last week which all are moving decisively towards a divided Europe, and that will only exacerbate this reversal.

It’s the election of Trump, it’s Brexit, it’s the rising political tensions globally, it’s Italy electing the anti-EU party, it’s Austria electing the anti-EU party, it is the wave we’ll continue to see across Europe, it is the election of strong men around the world.

A contraction in globalisation is, by definition, inflationary. And it comes at a time when the entire market is positioned for anything but that.

Fuel to the Fire: Rates

Now, adding fuel to the reversing of globalisation we have what is easily one of the most deflationary forces of all: the manipulation of interest rates by central banks to waaay below real rates, which has created a truly bizarre environment whereby market participants (due to recency bias) believe this will be sustained and continue forever and ever, amen. That looks like a terrible mistake to me.

The reversal of globalisation, trade wars, populism, and disruption to the global coordination we’ve been enjoying between policy makers and central banks are there for us all to see. And the ramifications promise to be quite extraordinary. A decade or two hence and we’ll all look back at this time and say, “Hell yeah, we could see that coming!” Hopefully you’re one of those those who does something about it.

And it’s no use us just saying, “Oh, those darned central bankers, cross-eyed fools that they are, it’s their bloody fault. Let’s rope them to the back of a truck and drag them about town for a bit.”

That would be cruel, barbaric and inhuman. It would cheer everyone up a bit, though so it’s got that going for it. But really it’s far better to look out for number one because let’s face it, nobody else’s going to do it for you.

Now, remember I talked about Japan repatriating capital during and after Black Monday?

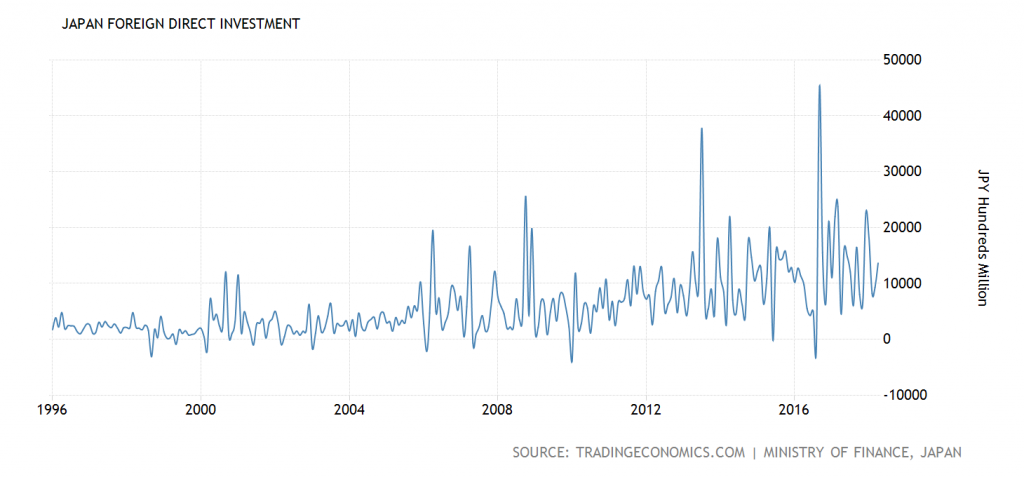

Well, today Japan is once again a large investor offshore. Both in the US as well as Europe.

So the question I ask myself is this, will the EU experience a “banking problem”, as discussed here and again here as we risk the following set of events:

- Rates rise externally in the Eurozone. It’s actually unlikely they’ll move slowly but rather once they go, they tip over all at once. Why? Well, you see, the “togetherness” that the pointy-shoed crowd in Brussels have fought so ardently for has a flip side to it. European debt and the outcome therefore of EU members is more intertwined with each other than that pen at the bottom of my wife’s handbag is with hair ties and God knows what else is in there. And we all know untangling this is impossible without dumping the contents of the handbag on the table. The European debt situation is my wife’s handbag simply with differing contents.

- Capital panics and leaves in search of “safer” climes. This would be the USD and the yen. Weird, I know, but remember all things are relative.

- Since this time around the shock to the system sits squarely in the sovereign bond markets, these are the very markets where fleeing capital likely chooses NOT to head for. The alternative? “Safe”, “stable” equities, cash, and commodities.

- With the euro falling vs. the yen, we could expect Japanese investors to do two things. First is to shift capital into US assets and the other is to repatriate capital to Japan. Now, you can be forgiven for thinking that this would be good for Japan. Remember, the capital in Japan has largely been invested in the bond market, but given that we’d be in an environment where a sovereign bond market is in free-fall, it’s not unreasonable to expect that returning capital to shy away from sovereign bonds of any stripe or description. No, instead I ponder, what if it heads into both the yen and equities, quickly driving inflation higher than the BOJ has ever imagined?

- With inflation now rearing its head (yes, even in Japan), the BOJ is now stuck with no tools whatsoever to tame it. And should that trade surplus turn into a deficit for any length of time… whoo boy, watch out! Because then we’ve a perfect storm ahead of us for the very market that’s confused the isht out of the best fund managers of our time: the great JGB market.

One thing I do know… As screwy as the US is, it’s more than probable it wins in the short and medium term here.

Japan, on the other hand, may well just be the country that gets tipped over, not from any dynamics happening internally, but from what happens externally. Remember, the blowoff peak in the Nikkei had its roots firmly set in Black Monday.

[clickToTweet tweet=”Japan may well be the country that gets tipped over, not from any dynamics happening internally, but from what happens externally.” quote=”Japan may well be the country that gets tipped over, not from any dynamics happening internally, but from what happens externally.”]

I’m not sure which is the bigger experiment. Brussels’ attempt to take what are basically a host of tribes, who’ve been kicking the snot out of each other for centuries, and get them all to cuddle and play nice under one roof… or Japan’s attempt to create inflation by destroying the bond market.

– Chris

PS: Before you go… This Friday I’ll be on a live call with our resident mining engineer Jamie Keech. We’re discussing the launch of our new research service and you’ll be invited to have your questions answered. Feel free to send through any you have ahead of time and then join us by registering here.

“There cannot be a crisis next week. My schedule is already full.” — Henry Kissinger