Jeezuz, it feels like it’s been ages. My apologies for the lack of articles of late. I’ve been spending a bit of time lately hurtling through the air in pressurised tin cans breathing recycled fart.

Speaking of which, last week we had a little round of drinks on a rooftop bar in Singapore for Insider members.

The view was gorgeous, the beer cold and expensive (hey, this is Singapore), but the most interesting thing was the folks who turned up.

I’d love to say that the night was filled with throngs of young, adoring, and extraordinarily pretty girls. But as cool as that would have been the world of finance is actually wayyyy more interesting than that. And so it was that we had a really eclectic group of folks turn up. Mostly middle aged men. And yes ladies, they were are all shockingly handsome.

One of those gents was a newly-minted subscriber whose buddy (an existing member) had convinced to join Insider. He’s a very cool guy who runs a global value focused fund and you can check out his musings here. I’m glad he joined the program and came to drinks since we had an enjoyable discussion. The topic: Turkey.

He’s bullish. I’m basically meh.

So since Turkey is clearly in crisis, I figured today I’d provide my thoughts on what crisis to buy and which crisis to avoid. A template, if you will.

By laying down my thoughts for critique it’ll open up a discussion. And since I love learning, what better way to do so than to tear your clothes off and reveal your underbelly. Here’s my underbelly on what crisis to buy and which to avoid.

————

Clearly buying into crisis in the past has produced some stunning returns, though, of course, not all crisis are cooked with the same broth.

So let’s begin with one that I think had I been in a position to do anything about I’d have bought with all the gusto of Pavarotti tucking into a bowl of pasta.

The Asian crisis, otherwise known as the Tom Yum Kung crisis.

Any crisis that’s named after Thai food should be on your radar. I mean, is there any food better than Thai food? It’s basically sex in a bowl or on a plate.

In any event, it was so named because the crisis emanated in Thailand, where the government was already bankrupt before the crisis erupted. As is the case with so many financial crises, this one had its foundations in leverage.

Thailand had accumulated a mountain of foreign debt. And when your debts are in one currency (in this case USD) and your revenues in another (THB), small adverse fluctuations in the currency begin to have an amplified effect on your ability to service your debts.

And so, when the inevitable happened (rising defaults on private loans), the currency came under pressure as foreign capital inflows reversed. That was the trigger for making Tom Yum Kung absolutely ridiculously cheap for foreigners. The baht collapsed from around 24 to 54 at the peak of the crisis.

It wasn’t just our Tom Yum Kung eating friends who got indigestion, as foreign investors quickly turned their attention to other Asian countries who had also indulged in the USD borrowing game. Here’s the USD vs the Malaysian ringgit.

Across Asia the forest fire swept and you could see the dry underbrush being built up well before the crisis.

Between 1993 and 1996 foreign debt-to-GDP ratios rose from 100% to 167% in the four large Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) economies and then shot up past 180% during the height of the crisis.

In South Korea, the ratios rose from 13% to 21% and then as high as 40%, while the other northern newly industrialized countries fared much better. Only in Thailand and South Korea did debt service-to-exports ratios rise.

Good Things Come from Crisis

Even better, the crisis toppled the Indonesian government.

Suharto, bless him, was forced out of office after 30 years of running his overly repressive regime. It was a darn shame he never got a bullet in his podgy ass or the blunt edge of a shovel to the head but at least he was toppled, and I’m reminded that you can’t always get everything you want.

This all came about due to the rapid inflation as the rupiah collapsed, sending hungry Indonesians into the streets waving their arms about and burning isht. It was a risky bet to make.

After all, who the hell knew what lay in store for an Indonesia post Suharto? Sometimes one dictator is simply replaced by another. In any event, Indonesia was a massive buy.

Then we can turn our attention to the Switzerland of Asia. Singapore.

They, too, did not escape the turmoil, though they fared much better than their neighbors. And by golly, if you ever get such an opportunity in your lifetime again to buy Singapore, for goodness sakes sell your kids clothing and buy the snot out of it.

Sure, the returns weren’t quite as fantastic than some of the their Southeast Asian neighbors but the risks with doing so where in order of magnitude lower.

If I look at all of the countries affected in the Asian crisis, much of what came about was NOT a direct result of government policies causing the crisis.

Furthermore, and perhaps because they realised they never had the firepower, the reactions to the crisis were largely market driven. The markets devalued the respective currencies, they took the pain, rebalanced, and then grew out of the crisis.

The rule of law and, most importantly, property rights remained as they were pre-crisis. This is important.

Now, let’s look at both Zimbabwe and Venezuela.

The crisis in both instances was entirely the direct result of batisht crazy government policies. Both countries implemented Marxist policies, changing the constitution in order to steal land, change ownership rights for select groups within the countries, and if we’re to boil it down to one thing, trampled on property rights.

Property rights are foundational to wealth creation. I explained it in a post on the importance of collateral:

Without collateral there is no trust, and without trust there is no credit, and without credit there is no leverage. And I’m not talking speculative “bet it all on black, sell the schleps another MBS” leverage.

I’m talking leverage of resources. I’ve got a lawnmower, let me mow your lawn, and you’re pretty good at math, so how about you teach my kids some math. That is leverage in its most basic form. It begins with leveraging talent, time, and resources. Africa suffers from many things but a fundamentally and tragically poor system of trust sits at the top and the consequences are that collateral is not created.

And so when the rule of law was eroded, property rights trampled on in both Venezuela and Zimbabwe the foundation was washed away. It was and isn’t a buy in my book.

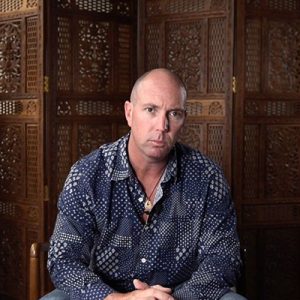

Remember, Venezuela began these policies way back in 1998 when Chavez was elected and eager to prove himself he subsequently quickly set about implementing a swathe of disastrous policies. The real effects of his socialist nonsense was largely masked as oil ran from $50 to $150.

But when oil came off the boil the real effects of Venezuela’s self inflicted pain was felt. It was, and still is, horrid. Like Horny Gold’s unsuccessful attempts at keeping her youth.

The reason I highlight both Zimbabwe and Venezuela is because in no particular order they did the following:

- Replaced congress

- Changed the constitution

- Granted themselves greater power over economy and judiciary

- Granted themselves the ability to stay in power for life. (though Zimbabwe did this via alternative means though the results were the same)

- Nationalised entire industries

And this brings me to Erdogan and Turkey where the signs are ominous.

And I’m not even talking about his pedophile mustache. I mean this just looks like a guy who, if he weren’t president, would be driving a van with blacked out windows, prowling the streets after schools out.

Like the Asian countries in the late 90’s, Turkey has enjoyed extraordinary debt-fuelled growth.

Unfortunately, unlike the Asian countries these are the least of our problems because true to his promise, Erdogan has appropriated to himself, by presidential decree of course, the right to hire the central bank governor, deputies, and monetary policy committee members for a four-year term.

Excellent! The once respected and independent central bank is now no longer respected, nor independent.

As per a Bloomberg article on the topic:

In an attempt to mitigate the systemic risk that Turkey’s corporate debt poses, the government has decided to restrict foreign-currency borrowing for some of the economy’s smallest companies all together starting in May, and to force larger borrowers to hedge against their exposure.

The corporate sector’s foreign-exchange liabilities climbed to a record $328 billion as of the end of 2017. Even when netted against their foreign-exchange assets, the shortfall has held near an all-time high of $214 billion.

As some companies struggle to repay on time, it’s putting pressure on bank balance sheets. The biggest lenders, including Akbank TAS, Turkiye Garanti Bankasi AS and Turkiye Is Bankasi AS, have already set aside cash for expected losses from a $4.75 billion default loan held by the majority owner of Turkey’s biggest telecommunications firm.

I know I’ve said it recently but the next step here is likely capital controls. Watch!

And so I struggle to get excited about buying this crisis. I want to buy crisis where the rule of law remains intact, assets simply go on sale, and we see forced liquidations. Then all it takes is having some firepower on the sidelines and seeing the opportunity for what it is while carefully analysing the risks such as government interventions which would threaten my capital.

Turkey is too risky for me. Braver folks may disagree and make a killing here.

– Chris

“This (presidential) system will not bear any resemblance to dictatorships under the same name in Africa and Asia, (It) will be unique to Turkey, it will be like a bee making honey, taking something from every flower and giving us a taste of a truly different honey.” — Recep Tayyip Erdoğan